Atomic Grayscale

The makings of a dangerous bubble

The Grayscale Bitcoin Trust has had a wild ride. Its price appreciated over 4.8x in the span of less than five months (only to give more than half of that back by mid-summer). Some still believe there is still explosive upside in GBTC and Bitcoin due to its "unique" structure.

The Grayscale Bitcoin Trust, as the name implies, invests in Bitcoin. But it is structured as a quasi ETF, quasi closed end-fund.

It works like this:

The trust first vets certain sophisticated investors as "authorized participants." The trust then issues shares to these participants in exchange for Bitcoin. As the trust increases its holdings in Bitcoin, it increases its share count (sort of like an ETF). The only catch is that these authorized participants must hold on to their shares for at least six months.

As the price of Bitcoin surged, so did investor demand for GBTC shares. The trust issued more and more shares to its authorized participants, who had to acquire more and more Bitcoins, which increased the price of Bitcoin, keeping the demand flywheel going.

These authorized participants made a killing using sophisticated trades to borrow Bitcoin, selling it to the trust at a premium and then unwinding the trade six months later, usually at a much higher price.

But unlike an ETF, the trust does not have a mechanism to redeem shares. So when authorized participants or investors want to sell their shares, they do so in the secondary market, selling to other investors. This means that inflows into the trust created demand for Bitcoin, without corresponding outflows when investors want to sell. All that Bitcoin just stays in place.

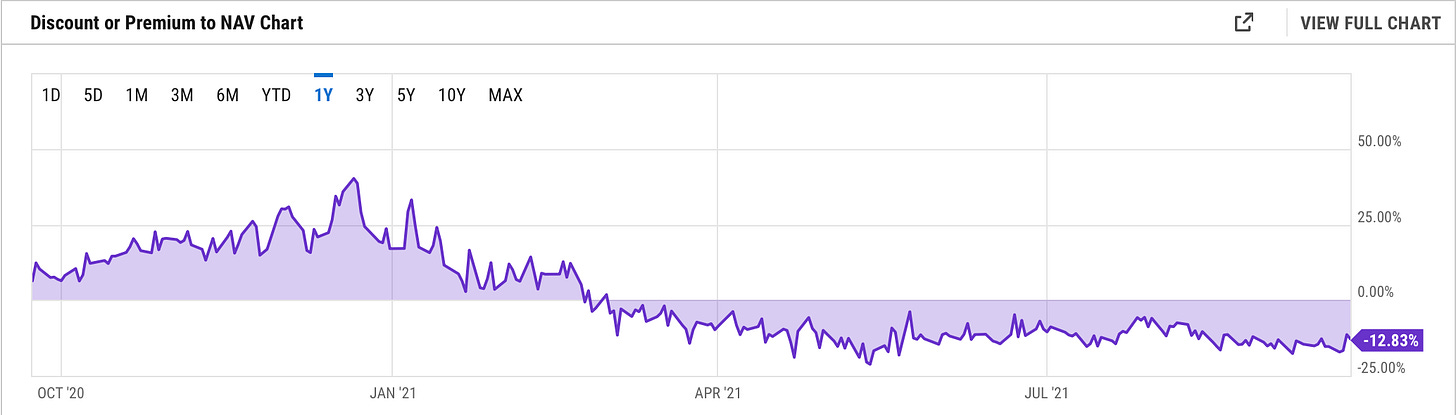

The result is a fascinating dynamic. As the trust gathered more and more assets, i.e., acquired more and more Bitcoin, it did so with no apparent mechanism to sell them and put them back into circulation. So the price of GBTC can have a significant mismatch with the trusts NAV. In fact, GBTC shares went from a premium of 40% in late December 2020 to a 15% discount today.

Here’s a chart from YCharts:

Think about what that does to Bitcoin's investment thesis. One of the premises of Bitcoin is that the supply of Bitcoin is limited to a certain amount of new coins each year and capped forever at 21 million Bitcoin. Subtract an unknown amount of Bitcoin that's lost forever due to forgotten passwords, stolen drives and plain old bad luck, and the total supply is still smaller. Now, subtract the 589,616 Bitcoin the trust holds and cannot sell in the foreseeable future.

That's just under 3% of all the Bitcoin that will ever exist and more than 15 days of trading volume — a massive amount in any context. And Grayscale is not the only long-term hodler.

As of today, the trust has suspended private placements. But that may change, creating further long-term demand for Bitcoin. And the opposite is also true. The trust may institute a redemption mechanism through which it sells its Bitcoin in the open market. However, I think this is highly unlikely given that Grayscale Investments, the trust's sponsor, earns a 2% fee on the trust's holdings. Why would they reduce their asset base and cut their recurring fees?

I believe this dynamic, among other forces playing on Bitcoin, place significant upward pressure on the long-term price of Bitcoin. And remember, this all works on an asset of dubious value at best. What would happen if this same dynamic repeated, but on a real asset? What if it happened on an asset that had very inelastic demand? What if it happened on an asset whose end-consumer cannot forgo acquiring it, cannot use a substitute or postpone purchases for a long time? What if, further, the supply of this asset was already constrained?

It’s happening again

Well, all that is playing out in the uranium market.

Uranium in the form U3O8, after refining and enrichment, is the primary source of fuel used in civilian nuclear reactors around the world. It is a notoriously opaque and complex market, where buyers are not sensitive to price changes. It's not like they can forego purchasing fuel for their reactors or decide to burn trash instead. Plant operators usually enter into long-term contracts with suppliers and occasionally acquire uranium in the open market.

Production, as you can imagine, is a complex undertaking. New uranium mines take years to prospect, design, permit and build. There's usually a lot of local opposition to new mines, which can delay or derail projects. Then there's the whole refining and enrichment process, followed by transportation to the end-users. In other words, supply is slow to react, especially to the upside.

Uranium is coming out of a long and painful bear market; from a high of $140 in 2006, to a low of $17.50 in 2016. As profitability fell, several large producers temporarily shut their mines, while others closed them permanently, and all froze all new mine projects. This environment has restricted supply and, more importantly, producers' capacity to respond quickly to increased demand.

There are, of course, other sources of supply. First, there's a large stockpile of reserves. Also, weapons-grade uranium from nuclear arsenals can be decommissioned and repurposed for use in power plants, but this is a marginal source of supply. And even nuclear waste can be processed into plutonium for use in some power plants.

So what changed?

After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, many countries decided to scale back their nuclear energy ambitions. Germany went all out and decided to shut all its reactors by 2022. In 2000, 30% of electricity produced in Germany came from nuclear power. By 2020, that share had fallen to 11% and still plans to reach 0%.

But setting Germany aside as an overreactive, ahem, outlier, other countries are going in the opposite direction. According to the World Nuclear Association, there are 57 reactors under construction around the world. With 442 reactors already operating, that represents an increase of 13% in the number of reactors and a 14% increase in generation capacity.

Demand for electricity, in general, continues to rise with no end in sight. How are we to meet this demand?

The long-term case for uranium and nuclear energy in general is that there is currently no way to meet expected electricity demand while hitting climate change goals without using nuclear power. Wind and solar are excellent sources and are getting better, but they suck as base-load producers. The only energy sources that can substitute coal and gas-powered plants as base-load generators are nuclear and geothermal, and geothermal is still in its infancy. So the demand for nuclear fuel is there, is likely to increase and remain inelastic.

But there's a new wildcard, and that's speculative buying.

Financial speculators have long messed in the big commodities markets, be it oil, gas or corn. But uranium is different. Taking actual possession of uranium is no simple feat, so investors have pretty much stayed away. If you wanted exposure to the price of uranium, you had to buy illiquid uranium futures or buy shares in a miner or refiner or, if you were lazy, a uranium ETF.

Until now.

Enter Sprott

The Sprott Physical Uranium Trust is a closed-end fund set up to acquire physical uranium in the open market and store it. Like Grayscale, special qualified investors deposit funds into the trust in exchange for newly issued shares; then, the fund goes out and acquires physical uranium and stores it in special facilities in locations across the world. Those qualified investors can then sell their shares in the open market, where anybody can buy them at a discount or premium to net asset value and participate in uranium price movements.

The fund began operations early this year and has seen massive inflows. It has purchased a lot of uranium in just a few months, just under 29 million pounds of it. As of the time of writing, the fund does not have a mechanism in place to redeem shares, so like Grayscale, purchased uranium is essentially out of the market. The trust becomes a new source of demand and competes with end-users for limited supply.

The worldwide production of uranium in 2020 was about 124 million pounds and about 25 million pounds a year from secondary sources. Worldwide consumption, on the other hand, was around 190 million pounds. This means that there is currently a shortfall of about 41 million pounds a year, which is filled by eating into existing inventories. How long can this last? How will that shortfall change as new reactors come online, and no new mines are not yet producing? What happens if the Sprott Fund accelerates its purchases or if similar vehicles create artificial demand?

This smells like a bubble in the making to me.

But what will this do to the long-term price of uranium?

It's impossible to say, but the obvious guess is that it puts pressure on the upside. In the grand scheme of things, the long-term price of uranium will still be determined by the development of the nuclear energy industry. The Sprott Physical Uranium Trust will likely play a small role, in that it may distort prices for short periods.

The question is: how long until inventories and reserves run out? Will additional supply be available by then? What happens if power plants can't find the fuel to keep reactors running? What will governments do?

I'll let you ponder these scenarios. And remember that this is not investment advice. I'm not suggesting you go out and buy any of the securities mentioned here; you must do your research and make your own decisions. I'm long both Grayscale Bitcoin Trust and Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, but I may change my mind as things change.

Caveat emptor.