Put Some SPACs in Your Step

Why all the rage in SPACs?

To the uninitiated, the explosion in SPACs may seem even more puzzling given the dismal returns most of these have shown investors. Well, retail investors, at least.

SPACs have made a ton of money for sophisticated investors who get early access and, of course, for sponsors.

So what, exactly, are SPACs, and how do they work?

The acquirer's dream

A special purpose acquisition company is, at its simplest, a public company set up for the sole purpose of acquiring a company. They're also known as blank check companies, in that, immediately after going public, they have no operations or assets, save for the capital raised in the IPO. Again, the idea is to use that capital to make an acquisition. What acquisition is to be made is not known at the time of the IPO.

When a SPAC goes public, most, if not all, of the raised capital is deposited in a trust. That money can only be used for an acquisition approved by investors. Investors get their money back if a suitable target is not found and approved within two years of the IPO. If a target is found and approved, the deal goes through, and the acquired company merges with the SPAC and immediately becomes a public company.

But, the devil is in the details and that's where the smart money makes, well, its money.

Meet the sponsor

The first character in the SPAC play is the sponsor. This is the person or institution that decides to launch a SPAC and does all the work: hiring advisors, lawyers and bankers, raising capital and finding and acquiring a target company.

The first step is incorporating an entity, the actual SPAC, and putting up initial working capital. This startup capital is known in the industry as "at-risk capital" because it does not have the right to demand redemption. In other words, if the search for an acquisition fails, at-risk investors lose their money. In exchange for this added risk, at-risk investors get a steep discount to the standard IPO price of $10 per unit. They get to purchase their units at $2 to $4 and are subject to a one- to two-year lockup.

One unit is usually equal to one share plus a fraction of a long-dated warrant. Warrants can be separated from the shared after a predefined period from the IPO, usually 52 days.

The sponsor can provide the risk capital itself or raise it from outside investors. But it is usually a combination of the two. This startup capital ranges from 2% to 7% of all the raised money. Of course, these aren't retail investors. These opportunities are only open to sophisticated and well-connected investors, such as hedge funds and large family offices.

The sponsor files an S-1 with the SEC as a SPAC. It selects a preferred industry and geography but uses careful wording to allow it maximum flexibility. A tech-focused SPAC can end up acquiring a gravel pit if that's the only acceptable target it can find. The review process for a blank check company is much simpler and streamlined than a traditional IPO. Instead of the usual 12 to 18 months, this process takes 4 to 6. But don't be fooled by this. Simpler and quicker does not mean easy. It's just less complex.

The sponsor should not have a specific target in mind at the time of filling. If it does, it must disclose it to the SEC, which will then evaluate the target company as a plain-vanilla IPO, complicating the process.

When and if the SEC approves the S-1 filling as effective, the SPAC goes public. Units are sold to IPO investors at $10 each and then begin trading freely on an exchange. IPO investors don't get a discount on the units, but they have redemption rights at $10 per share. Deals are structured so that the sponsor retains a ~20% stake in the SPAC. Sweet deal.

Notice it's $10 per share, not per unit. IPO investors can separate the warrants and sell them in the open market. They can then redeem their shares, and whatever income they get from the sale of warrants is pure profit; risk arbitrage at its finest. Again, retail investors don't have access to IPO prices and can only acquire shares in the secondary market and usually do so without warrants. And often, they buy-in at a premium to the $10 redemption price.

No wonder SPACs are bad investments for the average Joe. Buying SPAC shares in the secondary market is a terrible idea. You get very little downside protection, and the upside is iffy at best. It all depends on the sponsor finding a good target, negotiating a good deal, having it approved, executing the transaction and then executing on the business side. Too many things have to go right. All other investors have ample margin of safety, downside protection and either steep discounts or arbitrage opportunities.

The second act

The sponsor now directs its attention to finding a target. At-risk capital pays for search and compliance expenses, which is why it is not guaranteed and has no redemption value.

The 18 to 24-month window sounds like a lot, but finding a good target at a reasonable price is hard, especially with so much competition. Sellers know the SPAC is under pressure and with millions of dollars burning a hole in their pocket, something they will take full advantage of. Also, blank-check regulation states that at least 80% of the capital raised must be used towards an approved acquisition, effectively putting a floor on the size of the target. On the other hand, if the sponsor finds a target with a larger price tag than the equity raised, it can upsize its offering with PIPE investors.

As the name implies, a private investment in public equity, or PIPE, is a private placement of public shares. Again, these are only available to well-connected investors and are sold with favorable conditions, such as a steep discount or additional warrants.

This sounds expensive to the SPAC. Why would a sponsor want to do this?

Because PIPE investors usually help to stop-gap a SPAC.

When the sponsor finds a target it likes, it submits the acquisition to a vote. A predefined majority of shareholders must approve the deal. If the deal is not approved and the search period is nearing completion, the sponsor may request an extension. The sponsor must return all the IPO funds to shareholders if none is granted, liquidating the SPAC.

If the deal is approved by a majority of shareholders, those who voted against it can still demand the redemption of their shares at $10 each. Many IPO investors participate in SPACs with the blind intention of demanding redemption and simply making a risk-less profit on the sale of warrants. This means that, even though the deal was approved, enough investors redeemed their shares that the SPAC does not have enough funds to close the acquisition. That's where PIPE investors come in. They can make up the difference in exchange for generous terms and access to non-public information.

Closing

Once approved by shareholders, the SEC gets a final say on any deal. Assuming that happens, the trust releases the funds and the SPAC merges with the target company, usually changing its name and ticker symbol.

And voila! The target is now a publicly-traded company and the sponsor owns a considerable take. At-risk, IPO and PIPE investors also made a killing along the way. Now rinse and repeat.

Way to go, boys!

Boom times

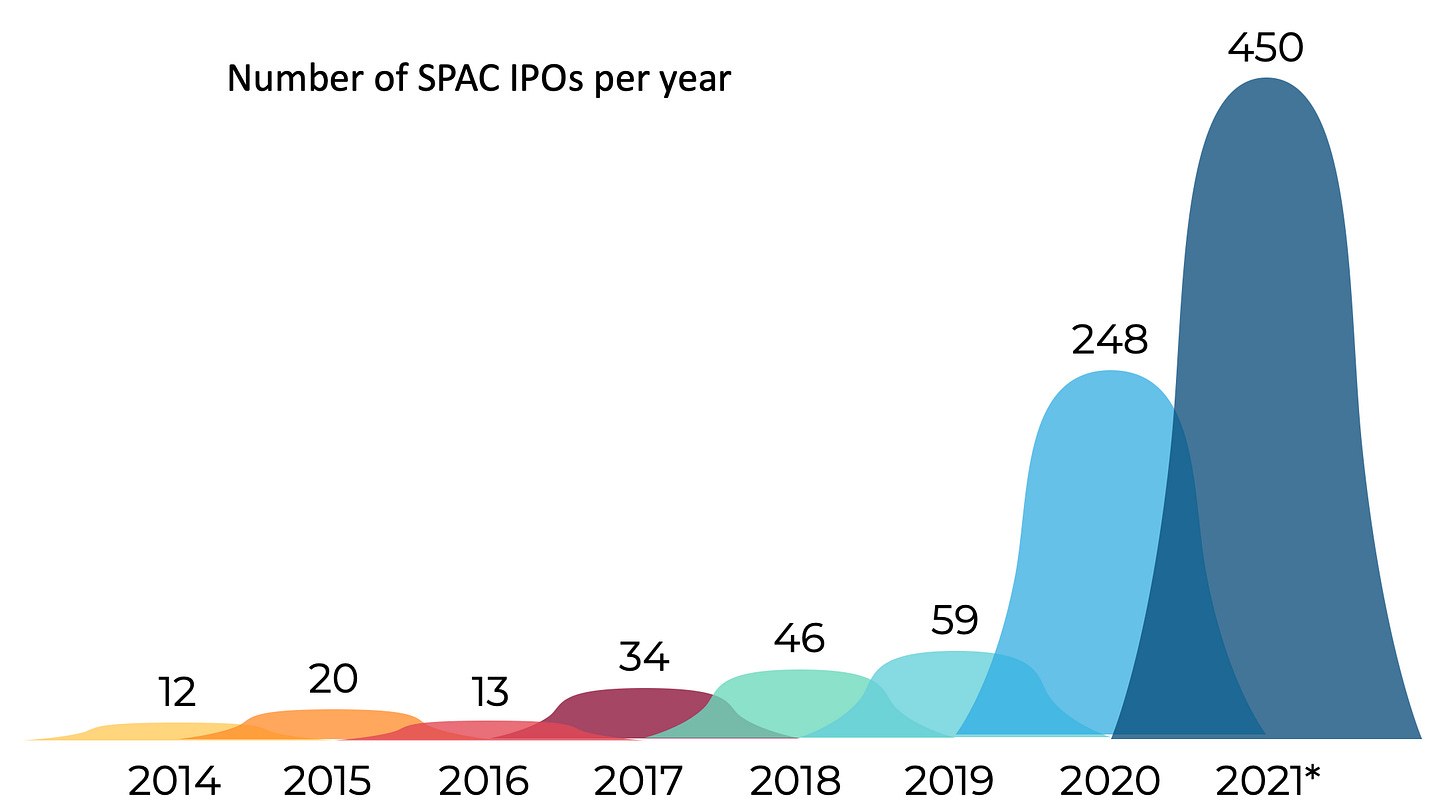

SPACs have been booming.

Source: spacanalytics.com

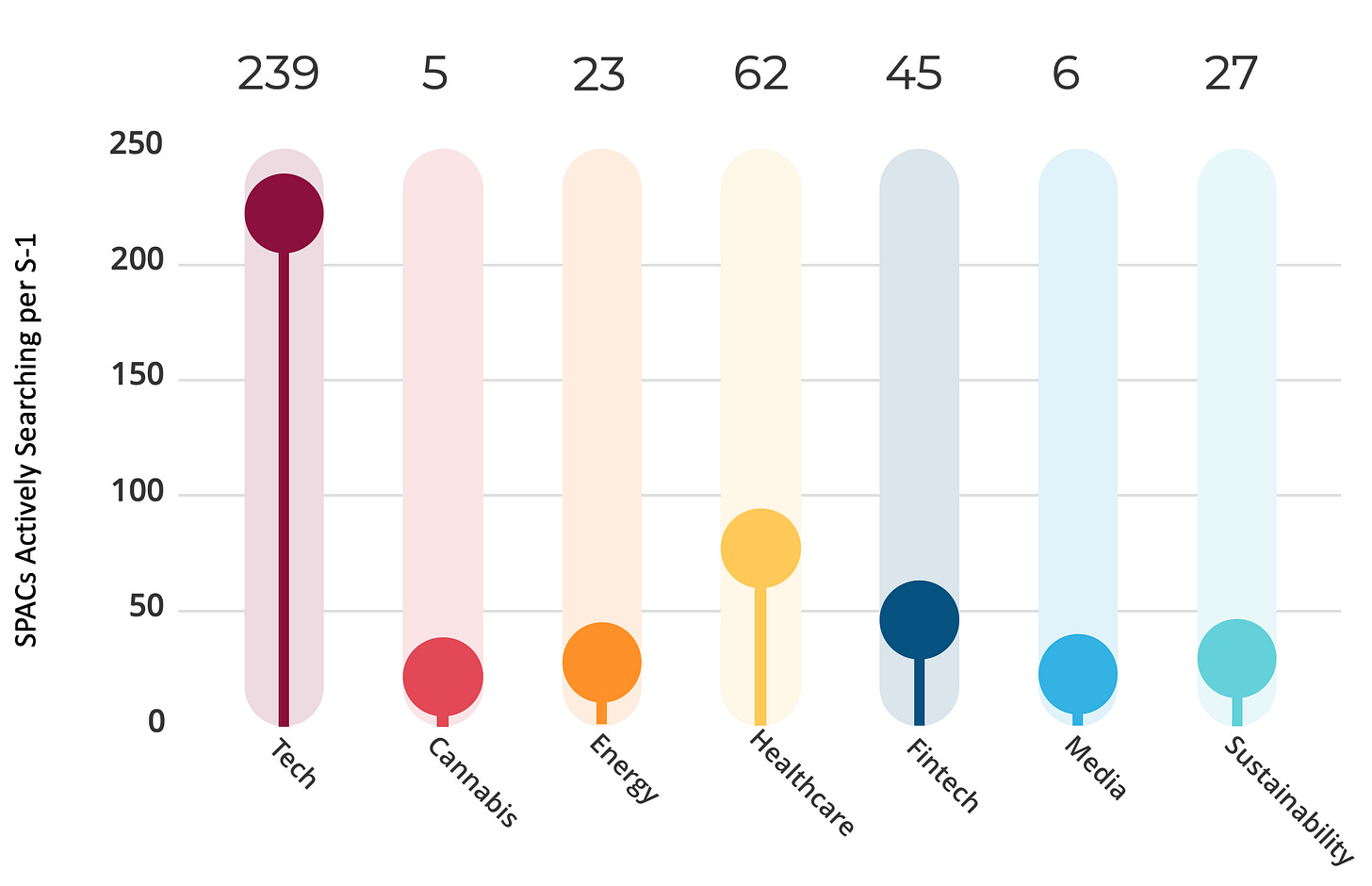

Not only are there more deals being done, but the average size is getting larger. 407 SPACs have IPO-ed and are searching for a target.

Source: spacanalytics.com

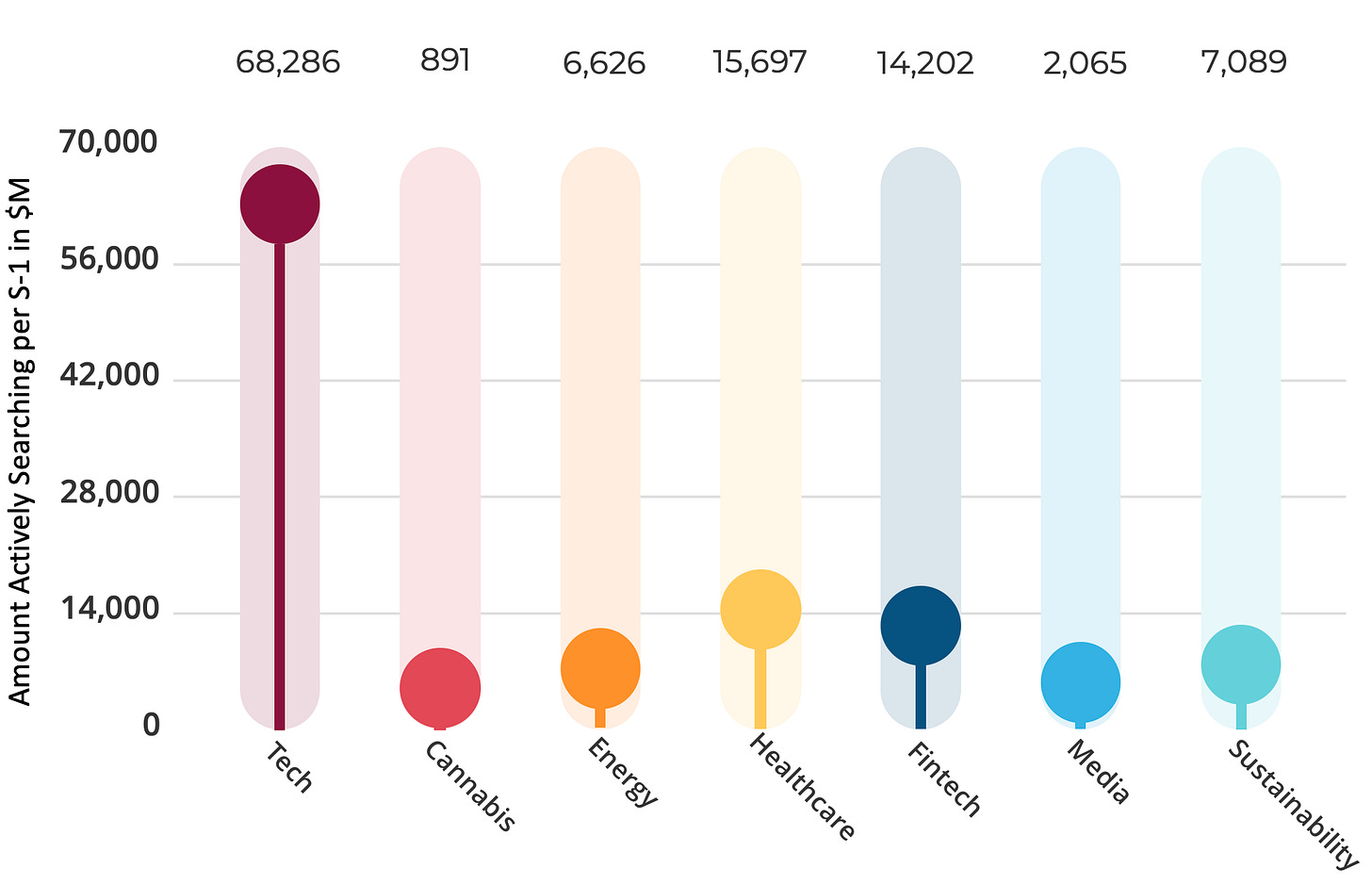

That’s $114.8 billion waiting to be deployed.

Source: spacanalytics.com

A lot of people find this boom surprising. You shouldn't. Everybody is making a killing except the dumb money, as usual. Why would you stop doing these deals if you had access to them?

Many factors set off this boom, but the most important one is regulation. The SEC changed SPAC rules, made them more transparent and, by extension, made them respectable. Goldman Sachs went from a "no SPAC" policy to underwriting and sponsoring SPACs in a few years.

The process sounds simple, but it's a real challenge if you are not a part of the old boys club. As the sponsor progresses through the steps described above, its position becomes more and more vulnerable. If bankers did a poor job selling the units, an uncomfortable percentage of shareholders might choose to redeem their shares, sometimes blindly.

But it's not all easy sailing. The SEC is concerned with the pace of filling and is increasing scrutiny. It has also made ambiguous changes to the accounting of warrants, leaving sponsors, accountants and lawyers confused. Also, as competition increases, so do acquisition valuations, and the market feels crowded.

But none of this is an issue to those connected investors that have access to these deals. And the SPAC acquisition process is quicker and smoother for most companies looking to go public, which is why I believe these deals will continue. It's a sweet gig if you can get it.